It is almost impossible to summarise the history of Lancashire in one page on this website but below is perhaps the most comprehensive but condensed that I have been able to find. I can also recommend the following book which is a detailed and thorough good read – “A History of Lancashire” by Alan Crosby published by Phillmore.

You will also discover much of the county’s history in the individual stages of the Walk, which highlight many historical points of interest!

Below is a comprehensive plotted history of the region courtesy of Lancashire County Council.

Palaeolithic culture flourished during the Pleistocene, when glaciations were interspersed with long periods of slightly warmer climate. Britain was still joined to continental Europe at this time and in periods of intense cold – such as the last glaciation 25,000–12,000 years ago – populations retreated to the warmer parts of the continent; although even during the glacial periods they made seasonal food gathering forays into the area that is present-day Britain.

Evidence has been discovered at Poulton-le- Fylde where a skeleton of an elk was unearthed which displayed evidence of hunting. It is thought that the elk survived being hunted, but that it escaped and died of its wounds, sinking into a muddy pool complete with one of the hunters spearheads.

Apart from this find, evidence of this period is relatively unknown in Lancashire although recent work in the wetlands has indicated that further investigation may reveal more evidence of occupation. For instance evidence of Upper Palaeolithic activity was discovered on the fringes of the permanent snowfields of the Lake District and in the tundra around what is now Morecambe Bay.

Gradually, as the climate improved at around c.8500 BC, the glacial ice sheets retreated and meltwaters separated Britain from the Continent. The climate became warmer and wetter and by c.6,500 BC pine forests had given way to denser, deciduous woodland. Oak and elm would have occupied slightly

better drained slopes, whilst exclusively oak woodland was predominant on poorly drained low-lying ground.

The Mesolithic is far better represented in the archaeological record than the Palaeolithic. The improved climatic conditions suited settlement by large numbers of people and bands of hunter gatherers roamed the upland and lowland landscapes of Lancashire following the herds and collecting wild food. A site at Rushy Brow, Anglezarke showed remains of temporary shelters and flint implements. It is thought to represent a temporary hunting camp of this period. Flint scatters discovered in the uplands between Saddleworth and Burnley, indicate that there were other seasonal summer hunting camps in the hills. These are important finds as some of the flint and chert implements were from Lincolnshire and east Yorkshire and indicate that regular long distance trade had already become established during the Mesolithic.

A shift from hunting and gathering to a settled agrarian society characterises the Neolithic period. In the archaeological record, this change is manifested by the appearance of new artefact types – querns, sickles, pottery and polished stone axes which began to replace the cruder tools of the Mesolithic period. Neolithic finds are more widespread than those of the earlier Mesolithic and may indicate more successful clearance and settlement of the densely wooded lowlands.

Environmental remains, such as pollen from the lake muds and peats of the Lancashire mosses confirm that vegetation cover was extensively altered by the arrival of farming. Climatic deterioration in the latter part of this period into cooler wetter conditions probably combined with human clearance of the forests and the impact of their grazing animals to reduce tree cover and encourage the formation and growth of peat mosses across large tracts of the county. Sophisticated stone axes, arrowheads and other implements provide evidence of Neolithic occupation throughout Lancashire. Evidence of trade is shown by the finds of stone axes from the Langdale area of Cumbria . Elsewhere in the UK new types of site emerged in the Neolithic, including permanent settlement and large ceremonial monuments, although evidence is rare in Lancashire. There is evidence of burial in large ridge cairns however, for example at High Park, above Leck Beck.

Metalworking technology, along with new types of flint-tool and pottery design were introduced from continental Europe at the start of this period. Cereal crops and stock rearing remained the mainstays of the economy, although changes in social organization were reflected in the increasing numbers of burial and ceremonial sites with round barrows and cairns, which many archaeologists now see in the context of ritual landscape form. These are evident throughout the Lancashire landscape.

In the Late Bronze Age, radical social and economic change led to the declining use of cairns and round barrows in favour of cemeteries which are less traceable features, and to the introduction of new ceramic styles, including jars, bowls and cups. Evocative sites dating from this period can be found at High Park, above Leck Beck and at Portfield above Whalley, where settlements suggest occupation from the Neolithic. During this period, the continuing deterioration in the climate to colder and wetter conditions appears to have forced early Bronze Age farming activities down from the higher fells, which may have been utilised for formal or informal pastoral farming by the end of the period.

Accidental finds in the mosses of the Fylde and south of the Ribble, where conditions are right for preservation of organic matter, have revealed bog bodies, burials, traces of wooden structures and trackways, as well as implements of stone and bronze. At Preston Dock in 1855, 30 human skulls were discovered along with two dugout canoes, 60 pairs of deer antlers, 43 ox skulls, two pilot whale skulls and a bronze spear head. These finds may possibly indicate the presence of some sort of marsh dwelling.

Iron working was among the new technologies introduced to Britain from the continent in the Iron Age period. Population growth led to competition for land and the development of a more territorial society; hillforts and defensive enclosures were manifestations of this social shift. Nothing is known of the political or territorial organisation of the area until just before the Roman conquest although it is known that most of the region was controlled by the Brigantes. The Setantii, one of the smaller tribes ruled by the Brigantes, are believed to have occupied the Lancashire Plain and its adjacent foothills.

The visible remains of the Iron Age within the landscape are generally confined to hillforts at Castercliffe and Warton Crag and a number of defended farmstead sites.

The Roman invasion of Britain started in AD43 with a landing on the south coast. Pacification of the indigenous tribes and the establishment of client kingdoms on their fringes progressed over the years, with the establishment of formal tribal capitals (Civitas) in romanised towns and a military road network, guarded by a series of forts. In Lancashire Roman military y activity may well have slightly preceded the formal and well documented advances of Agricola in AD79, although traces are few. Agricola’s campaigns, which may have been prompted by the destabilisation caused by internal conflict within the controlling Brigantian tribe, utilised ship-borne troops who landed in the estuaries as well as a land army. Forts were established or formalised at Dowbridge near Kirkham, Ribchester, Lancaster and Over Burrow, although the first of these seems to have had only a short life.These sites seem to have been rebuilt during the AD 120s and a military style although not necessarily formally fortified industrial settlement was established at Walton-le-Dale, probably to supply goods to the Roman Army.

Pre-Roman settlement was widespread and continued under Roman occupation. Some of the native populations were relatively unaffected whereas others took advantage of opportunities for trade and adopted more Romanised practices. Roman army engineers built more substantial roads with metalled and cambered surfaces, to expedite the movement of soldiers, food and equipment. Naturally these roads were also exploited as trade and communication routes. The Roman road network in Lancashire grew around the principal south-north route from Manchester through Ribchester to Over Burrow and Cumbria and the west-east route from Kirkham-Ribchester along the Ribble Valley into Yorkshire. Some sections of these roads were quickly abandoned for long distance travel and are consequently well preserved and can be traced for miles; others, including routes, which stayed in use and were thus worn out and rebuilt on many occasions, can be difficult to trace. Another road travelled from Manchester to Lancaster along the margin of the plain although details of its route are uncertain. Despite their low survival rates, Roman roads can be seen in the course of modern routes, lanes and in the lines of hedges and field boundaries. Their alignments are important and tangible traces of occupation and movement.

The Roman empire was in decline by the fourth century as barbarian raids exploited weaknesses in the empire caused by political instability. At Lancaster the fort on Castle Hill was reconstructed about AD330- 340, probably to defend against sea-borne raiders from the Irish Sea. The economic disruption and endemic insecurity stopped the growth of romanised civilian settlements such as Lancaster, or caused their abandonment and, after AD 400, the economy is likely to have been almost completely agricultural and rural. For the majority of the Lancashire population, lives would have continued as they had done before the Roman conquest. By the middle of the 5th century direct Roman rule had been replaced by local governance and the armies had retreated to defend more important frontiers.

After the Roman occupation much of the Roman infrastructure ceased to be used. Prior to the Norman conquest, Lancashire was influenced by Saxon and British realms. Place names prove to be one of the few sources of information about these societies as they did not keep documents. They suggest that well into the seventh and eighth century the county was populated by British speaking peoples. Places such as Pendleton, and Penwortham, contain the British word ‘penno’, which means a prominent steep ended hill. The best known of these is Pendle Hill, which can be literally translated to ‘hill, hill, hill’ as the Saxons added the suffix ‘hill’ to its original British name ‘Penno’ producing Pennehill, which was later corrupted to Pendle and which has become known as Pendle Hill.

A significant number of place names display combined British and Anglo Saxon influences and by the late sixth century the tribal kingdoms of North Lancashire were absorbed into Anglian Northumbria. Lancashire south of the river gradually became incorporated into Northumbria and after a time Mercia.

Conversion of the Anglo Saxons to Christianity had begun in 620 and many place names ending in suffixes of ‘hamm’ (as at Kirkham and Heysham) and ‘tun’ (as at Halton and Preston) indicate centres of importance containing early churches, which governed wide tracts of the surrounding countryside. Place names containing ‘ecles’, which in Celtic languages is derived from the Latin ‘ecclesia’ meaning a place of worship, are evidence of early places of Christian worship within British settlements. Such settlements include Eccleston near Chorley and Great Eccleston in the Fylde.

By the ninth century place name evidence suggests a gradual and peaceful settlement of hitherto unused land by Hiberno-Norse peoples. The RibbleValley is likely to have functioned as a major routeway from the Viking York kingdoms to the Irish kingdoms. At Cuerdale on the banks of the Ribble in 1840, a massive hoard of Viking silver was discovered. It was dated to around 905 and contained coins from as far afield as Afghanistan.

Place name evidence is again testimony to the activities of a non documentary society, although it is likely that the new settlers renamed existing villages as well as establishing new sites. Goosnargh incorporates the personal name Gusan and Grimsargh that of Grimr. In south west Lancashire the suffixes ‘by’ meaning farm (Formby, Crosby and Roby) and ‘skeith’ (Hesketh) which itself means a place for horse racing, both indicate Scandinavian settlement. In the north, place names of ‘Ireby’ (farm of the Irish) indicates settlement by Irish Norse men and other suffixes such as fell, force, gill, thwaite, beck and dale indicate more general Norse influences.

At the time of the Norman Conquest there was no administrative district of Lancashire, and within the Domesday Book, south Lancashire was described as inter Ripam et Mersham meaning between the Ribble and the Mersey. North Lancashire was described as the ‘Kings lands in Yorkshire’.

To ensure the security of this peripheral part of the Kingdom from the threat of attacks and uprisings, the English-held estates were confiscated and allocated to followers of the King. This was part of a policy of creating powerful lordships, which could act as a front line of defence against invaders and keep the local population under control. A number of castles were therefore built at strategic and dependable locations. The early type were motte-and-bailey castles positioned to control important routeways and the local population. An example is the well preserved Castle Stede, which was one of a string of at least nine castles on the Lune.

Roger de Poitou, under whom most of Lancashire was united in one lordship, established his capital manor at Lancaster by building a stone castle in this strategic location. Clitheroe was another important castle. It was located on top of the limestone knoll and controlled the important Ribble-Aire routeway.

The county was recognised in its own right in 1181-2 when an official of the royal exchequer wrote out a separate parchment in an accounts document headed ‘Lancasra quia non erat ei locus’ (Lancaster, because there is no place for it in Northumberland). Before this the area, which is modern day Lancashire was included in annual financial statistics wherever there was space on the parchment, rolls. After a century, this formally recognised Roger de Poitou’s land grant as a county in its own right.

Following the upheaval of the conquest, the reallocation of English Lands to French nobles and the subjugation of rebellions in the north, the medieval period was one of great prosperity with economic expansion and rapid population growth. The frontiers of settlements and agricultural activity were expanded to feed new populations; new settlements were established and more difficult terrain bought into use, wetland was drained, woodlands cleared and vast tracts of pasture ploughed up. This growth was however checked in the fourteenth century by a combination of disease, bad harvests and warfare. The Black Death, which ravaged the country between 1348 and 1351, killed half of the Lancashire population. This resulted in an important alteration in the balance of agriculture. Ploughing for arable crops was replaced by the extension of pasture for livestock farming, including large scale sheep farming to supply wool for the English and continental markets. Textile manufacture was well suited to Lancashire as the water was ideal for cloth making, and there were large tracts of land for grazing sheep. As a result of these factors, the textile industry expanded rapidly.

Over most of the county nucleated settlements were rare and most people inhabited small hamlets and isolated farmsteads. This pattern can still be seen in the countryside between Parbold, Mawdesley and Heskin and in much of the uplands. The exceptions to this pattern include the planned villages of the Fylde such as Elswick and Clifton.

In east Lancashire the ‘fold’ pattern was common and involved several cottages and farms sharing a common yard. Examples of this can be found at Horrocks Fold and around Wardle and Littleborough. In the uplands, where unfavourable soils, climate and topography discouraged arable farming, the ‘infield-outfield’ system was adopted. Crops were grown for subsistence close to settlements and the wider landscape was devoted to summer grazing. By contrast, in the lowlands, arable farming was widespread until demand forced a change to livestock and market gardening. Most lowland communities operated an open or common field system, although this was rarely the rigid three field system of the midlands as the scarcity of drier land meant that a fallow year was economically unviable. The legacy of ‘ridge and furrow’ earthworks, which result from ploughing in strips, confirm that the open-field system was present. The raised strips were preserved from later ploughing by the reversion to pasture. Beyond the open arable fields, many towns had areas of common pasture which were frequently referred to as ‘moors’, and are still identifiable in place names such as Moor End outside Halton in the Lune valley. Surviving relict medieval landscapes can be seen in many places, for example at Longton, south west of Preston, and in the Ribble Valley.

Many of the townships in lowland Lancashire also contained large areas of wetland. The Fylde, the shores of Morecambe Bay and the broad stretch of land from the Ribble through Ormskirk included vast areas of Mossland. These areas contained many pools and lakes; Martin Mere was at one time the largest lowland lake in England, extending for some six miles. These areas, although described as ‘waste’ in later centuries, provided important resources for rural communities. Peat was a valuable source of fuel, reeds were used for thatching and rushes for candles. Waterfowl and fish were important sources of year-round food and many acres of land were secured as rough grazing for livestock. Between 1100 and 1300 population pressures forced the drier edges of the mosslands to be regarded as potential farmland. The small scale drainage works to bring these marginal mosslands into cultivation were the precursor of one of the most important long term changes to Lancashire’s landscape; that of wetland drainage.

Woodland clearance also resulted from population pressure and was widespread in the 12th and 13th centuries along the fringes of the Pennines and Bowland. These clearances are evidenced in the numerous place names, which originate in this period, which include the term ryding (cleared land) such as at Ryddings Farm at Aighton, rod (clearing) such as at Blackrod and stubbing (clearing land of tree stumps) such as at Stubbins Nook which is near Longridge. The effect of this was the creation of a small scale intimate landscape of scattered farms linked by winding lanes and irregular fields with patches of surviving woodland on stream-sides and field edges. This landscape is still prominent in areas such as the Lune valley and the Ribble valley.

Medieval forests in Lancashire were located in the uplands. Forest in this period meant ‘land set apart’ and was subject to Forest Law. Woodland would have been economically important to medieval settlements as a feeding ground for swine, a source of timber for house construction, fuel, and bark for tanning, as well as for its forest animals. In Lancashire there were two main areas of forest. North of the Ribble were those of the Earldom of Lancaster which included Bowland and to the south were the forests of the Honour of Clitheroe which included Pendle and Trawden. It is probable that these forests were created soon after the Conquest as special hunting grounds. Gradually, local landowners created private deer parks which themselves became much desired features of country estates. As hunting declined in the wider landscape, vaccaries became more important. These were extensive carefully managed hillsides occupied by herds of freely wandering cattle.

Between the 12th and 14th centuries Lancashire formed part of the debatable border lands between the English and Scottish kingdoms. As a result, some of the wealthier inhabitants erected tower houses or dug defensive moats around existing halls.

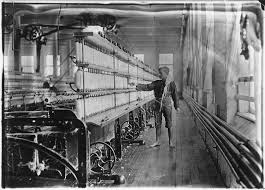

Many of the industries, which became important to the Lancashire economy have their origins in the medieval period. Deposits of iron ore were worked in this period and there is evidence of iron working at Pendle, Trawden, and at Quernmore on the western fringe of Bowland. Most of the coal fields were beginning to be exploited by the Middle Ages and stone quarrying was developing as a significant industry in this period. The most important industry however was that of textile manufacture, especially woollen cloths, linen and canvas. Spinning and weaving were undertaken on a domestic scale, although finishing and cleaning was carried out at a more industrial scale within water powered mills.

It is also in the medieval period that town life gathered apace and many of the great population centres acquired urban characteristics. Initially these were formed around the markets, which became established outside important churches or castles, such as Preston and Lancaster, or at manorial holdings, and soon exerted a strong pull over their surroundings. For example, surnames appearing in Preston during the medieval period suggest a large number of the town’s new settlers were being attracted from the Fylde and the Ribble Valley.

Lancashire’s early modern period saw a gradual progression from a predominately rural county with a traditional pattern of settlement and land use into a county of industry with large towns, high levels of literacy and well developed trade and communications.

Industrialisation with its origins in textile manufacture gathered pace. The domestic manufacture of woollen cloths and fustian gained importance and provided additional income for thousands of families otherwise engaged in agriculture. This dual economy made it possible for large portions of the Lancashire population to survive on otherwise non viable agricultural holdings. The rural landscape was in many places devoted to supplying the needs of the small scale industries; flax and hemp were grown in the west to meet the needs of the ‘linen men’ and other small scale manufacturers. Salt manufacture is noted as an important industry during this period There is evidence of early production from the extensive sandflats at Silverdale/Warton and Pilling/Cockerham. Salt was one of the few methods of preservation in the days before refrigeration and was extensively used as a means of preserving meat and fish.

Coal extraction similarly became more expansive and specialised to meet the demand caused by the rapidly growing population and a move to the use of coal rather than peat or wood as a domestic fuel. Deeper mines became possible with the invention of steam driven drainage pumps, and gradually became common on the coalfields.

Religion in Lancashire up to the early modern period was dominated by Roman Catholicism, although after the Reformation Lancashire developed remarkable religious diversity, particularly after the Toleration Act of 1690. Perhaps the most notable Lancashire example of this diversity is George Fox who in 1652, on the summit of Pendle Hill, experienced a vision, which later led him to the home of Thomas and Margaret Fell near Ulverston where the Quaker movement may be said to have been founded.

By the 1750’s most of Lancashire’s common arable and meadow was enclosed. This movement had a far reaching impact upon the moors and mosses as after the early 16th century, opportunities for greater financial returns from land drainage and improvement ensured many landowners saw reclamation of otherwise less profitable land as an attractive prospect. This was made possible and easier with improvements in technology as windmills aided increasingly ambitious drainage schemes by the early 18th century. These developments made drainage an important feature of the Lancashire landscape from the 17th century onwards. A notable example of this is the spectacular drainage of Martin Mere. Although some reclamation had begun during the medieval period, the pace of reclamation accelerated from the late 17th century and, despite being hindered by repeated flooding, was completed successfully by the 1850’s. The process was aided by steam pumps and produced a vast tract of highly valuable agricultural land.

The sheep population increased during the 15th and early 16th centuries in line with the expansion of the woollen and textile industry, although after 1600 a reduction of the industry resulted in a smaller demand for sheep in the south of the county in particular. Cattle gained importance and sizeable and profitable herds appeared the mid 18th century. Dairying emerged as the mainstay of the Lancashire agricultural economy, with beef herds being driven to markets in the growing towns to meet the demand of the rapidly expanding urban population.

During the mid 16th century, stone or brick became the preferred building material stimulated an ever increasing demand for stone and slate. Sandstone quarries in the south west, limestone quarries around Clitheroe and slates and gritstone quarries around Pendle all expanded rapidly. The majority of the half timbered halls were rebuilt, particularly in the south east of the county and now only their later stone and brick replacements survive. However the survival rate of stone and brick farmhouses is good and many remain visible today.

As industrialisation gathered pace, the transport of bulk commodities such as coal from south Lancashire, cloth from the east of the county and salt from the coastal saltpans became important. Roads were generally maintained by the manor or by religious houses prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s and early 1540s. Turnpike roads maintained by trusts and funded by tolls were introduced to the county after the 1720s. It is also around this period that schemes to improve river navigation appear.

The gradual developments of previous centuries accelerated from the middle of the 18th century, with rapid changes to create a dynamic, industrialised society. The large scale application of technology resulted in a move from a rural to an urban economy and placed increasing pressures on agriculture, mining, quarrying and the transport network.

Textile manufacture continued to dominate the economy of Lancashire and cotton began to become more important than wool as supply of raw cotton from the colonies became available through the ports, and the suitability of Lancashire’s damp, mild climate for spinning cotton became evident. Existing water power and labour allowed this shift to be easily made. Other locally important textile industries were: silk, produced at Galgate near Lancaster and sailcloth at Kirkham. Initially the mills were water powered and located in chains along valleys, although by the early 18th century steam power was being introduced This allowed mills to be situated close to canals and railways for easy movement of raw materials, finished products and the vast quantities of coal required by the boilers. Despite the introduction of steam power for spinning, hand looms were still used for cotton manufacture and for weaving cotton. Weaving became worth pursuing as a profession in its own right. This also required purpose built accommodation, including a loom shop, which was usually recognisable by its multiple windows. These ‘weavers cottages’ are conspicuous in the east of Lancashire. After 1830 however, the application of steam power to weaving resulted in large factory-style weaving sheds in the towns and the decline of the cottage industry. The weaving sheds with their north facing roof lights are still a feature of East Lancashire towns.

The improvements during this period of the county’s transport network were central to the success of Lancashire’s expanding industrial economy. The increasing globalisation of trade from Lancashire, principally with the West Indies and the Baltic, required the expansion and creation of ports such as Lancaster, Fleetwood, Heysham and Preston to meet demand. The Corporation built one of the largest and most ambitious docks in the country at Preston, which required the constant dredging of the Ribble and for which the town is still paying the debt charges. In Lancaster the establishment of St. Georges Quay in 1750-1755 reflected increasing prosperity. This was part of a boom,which the city enjoyed from the middle of the eighteenth century which has left a legacy of fine Georgian architecture. From the later 18th century the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Lancaster Canal were constructed. The construction of the network of Turnpike roads also accelerated in the 1750’s and an important second phase of road construction occurred between 1790-1842 when 750 miles of new road were constructed following relatively direct routes.

Lancashire occupied a pioneering position in the history of the railway network. Initially wooden tracks facilitated the movement of coal tubs in the Lancashire coalfield and the introduction of iron rails followed shortly after their invention. A wave of passenger lines was constructed between 1840-60 linking industrial settlements. In the latter part of the century they played a major role in the transport of people to the newly developed coastal resorts.

The population of Lancashire increased sevenfold between 1801 and 1901. This period of 100 years saw a shift from a 10% urban population to almost 90%. This necessitated the expansion of old settlements and establishment of new towns. In the late 19th century wealthy patrons and officials made efforts to create an urban identity and stamp mature civic pride on communities. The squalid slum areas were swept away for the construction of civic buildings and railway stations. By the 1870’s urban authorities passed laws imposing minimum building standards and by the late 1880’s neat brick terraces of houses were laid out to strict grid patterns. During this period quarries such as that at Britannia Quarries were blasted for gritstone, which was needed to construct churches, public buildings and the great feats of Victorian engineering such as the reservoirs.

Along the coast a string of resorts appeared after the middle of the 19th century to meet the growing demand for leisure and relaxation. Blackpool and Morecambe, along with Lytham and St Annes developed from agricultural and fishing villages and attracted visitors in vast numbers

The pressures of urban population growth on the rural economy were profound and lasting. Higher levels of demand created new incentives for investment and improvement in agricultural practices. In south Lancashire reclamation of mosslands continued and some of the best agricultural land in the UK was created. Market gardening emerged as an intensive industry during the early 19th century in areas around Ormskirk and Burscough. The improved communications were essential to the success of these ventures as they provided opportunities to import ash and manure as fertilisers and export fresh produce to the cities. In the Ribble Valley and the Fylde, a switch from arable production to raising dairy herds was an important development, caused by the growing demand for fresh milk in the cities.

From the end of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century pressure to create more productive arable land resulted in a dramatic new landscape of large square fields enclosing areas of previously open moorland. The geometric pattern is in evidence throughout the county; endless miles of straight stone walls and verged roads replaced pre enclosure tracks and less regimented field boundaries.

Up to this period the landscape was characterised by numerous small farms although, as the opportunities for wealth from farming emerged, many landowners looked to extend their properties by purchasing adjacent freeholds. Meanwhile, a traditionally conservative and catholic gentry sought to express their wealth by rebuilding country houses in fashionable styles. Between 1800 and 1880 dwellings surrounded by attractive parkland were developed throughout the county, although many in later years became too expensive to maintain and were sold for institutional uses.

NB:This extract refers to the County Palatine and not the present administrative boundary

In 1842 Barclay’s Complete and Universal Dictionary summarised the county as;

A county of England lying on the Irish Sea, and bounded by Cumberland, Westmoreland, Yorkshire, and Cheshire. It is 75 miles in length, and 30 in breadth. It is divided into 6 hundreds, which contain 27 market towns, 62 parishes, and 894 villages. This county comprises a variety of soil and face of country; there being mountains of more than 2000 feet high, in the north and eastern parts, with wide moorlands or heaths amongst them; extensive bogs or mosses, which yield only turf for fuel, and are very dangerous; and some most fertile land for agricultural purposes. it yields iron, coal, slate, and other building- stones; salt, &c. &c. Grazing is more attended to than agriculture. The fisheries, both in the rivers and the sea are valuable .As a commercial and manufacturing county, Lancashire is distinguished beyond most others in the kingdom. Its principal manufactures are linen, silk, and cotton goods; fustians, counterpanes, shalloons, baize, serges, tapes, small wares, hats, sail-cloth, sacking, pins, iron goods, cast plate-glass, &c. Of the commerce of this county, it may suffice to observe, that Liverpool is now the second port in the United Kingdom. The principal rivers are the Mersey,

Up to World War I Lancashire was considered to be a prosperous county, famed for its industrial and commercial power, unquestionable prosperity and proud cities, many of which had grown from humble beginnings only a century before. Following the war, foreign competition, diminishing overseas trade, outdated technology and rapidly decaying inner cities threatened to undermine its success. By the 1930s the county was suffering from a protracted depression from which it has taken half a century to emerge.

The inter war decline of Lancashire’s traditional industries was swift. Despite a brief boom following the war, cotton production fell dramatically. Some firms switched to synthetic fibre production, but nothing could be done to avoid the mass unemployment created by the collapse of the textile industry and its ancillary trades. Preston for example suffered 55% unemployment at this time.

Coal mining entered a rapid decline during the 1950s. This was largely due to the antiquated nature of many pits and to foreign competition, but also resulted from the un- avoidable problems posed by geology and a proven lack of long term resources. By 1960 almost all pits in Rossendale and mid Lancashire had been abandoned. Today no pits are operational save a small number of shallow, open cast workings.

By the 1930s unemployment levels were very high across the whole county and, as a means of reversing the trend, the government designated ‘Development Areas’ where newly locating industries could gain subsidies. However by the 1980s, these were phased out in favour of enterprise zones and development corporations, which encouraged regeneration through the private sector. These proved prosperous in the south west of the county, but less so in the north and the south east.

In recent years, sustained economic and employment growth have been concentrated in the service sector and light industry. Tourism, leisure, education, financial services, retailing and administration are also all increasing rapidly. In Preston for example, the University, Borough and County Council are by far the largest employers; the town is once again a service and market town, as it was prior to the Industrial Revolution 200 years ago.

The transport network, which grew in tandem with industrialisation, suffered as the post war decline became established. For instance in the first half of the 20th century, the canal network contracted and many miles fell derelict. This trend is however, being reversed with major schemes to rejuvenate the canals as a leisure resource. For example, a new stretch of canal is to be built to link the Lancaster Canal to the Ribble estuary. In addition there is potential for re-opening of railway stations in East Lancashire and on the west coast main line.

Despite a general decline in the transport network, the success and widespread appeal of the motor car has ensured a certain degree of growth. The 1920s saw dramatic new road schemes and later in the century the County Council planned a new motorway network. The Preston Bypass, the first motorway in the country, was opened in 1958 and in the following 20 years Lancashire saw the emergence of a well integrated transport network, which proved so successful that capacity was reached by the 1980’s and has required a major new improvement scheme.

Towns and cities have suffered profound and lasting change during the 20th century due to the combined effects of population decline, suburbanisation and economic change. Overcrowding problems of the urban poor were tackled by the urban clearance programmes of the 1950s and 60s, followed by the construction of large council estates and high rise flats, although the latter proved

so unpopular that many have since been demolished. The creation of overspill communities was also tried, building on attempts in Manchester during the 1930s. As a result Skelmersdale was constructed to accommodate 70,000 of overspill population from Liverpool and rejuvenate a small mining community, which was suffering severe unemployment problems. The last quarter of the twentieth century has also seen an attempt to link Preston, Chorley and Leyland into a city of fi million people called the Central Lancashire New Town. New industrial areas were constructed but the vision failed to materialise as the fashion for new towns faded.

The major industrial centres all suffered wartime bombing, although towns such as Preston and Blackburn escaped serious damage. These towns were substantially remodelled as a result of post war planning schemes in which 18th and 19th town centre buildings were cleared and replaced with contemporary structures.

During the 1960’s nuclear industry arrived in Lancashire with the construction of the power station at Heysham and the B.N.F.L plant at Springfield in the Fylde. In more recent times wind farms have begun to appear on the west facing moorland summits providing green energy for the flourishing Lancashire population.

The countryside, despite the effects of intensification and the application of new farming methods since 1939, has enjoyed a great deal of protection, with the designation of large areas such as the Forest of Bowland, and Arnside and Silverdale Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Other areas also enjoy protection for ecological and geological reasons such as the marshes and mud flats of the Ribble estuary and Morecambe Bay, the limestone pavements of Silverdale and the moorlands of Bowland and the South Pennines.

Enjoyment and management of the countryside for recreational purposes has been promoted since the late 1960s, with the opening for example in 1970 of the Beacon Fell Country Park and the provision of countryside recreation services particularly in the West Pennine Moors and the AONBs.